Please consider donating to Mutual Aid LA, which is redistributing funds to people affected by the Eaton and Palisades fires, and to Mask Bloc LA to get respirators to those who need them.

There are two places I feel like I come from. Not the countries my family emigrated from—France and Wales on one side, Poland and Lithuania and Scotland on the other—but the places my family has called home in living memory.

One is a sliver of Quebec between Montreal and the US border, where most of my mother’s large family still lives. The other is across the continent in southern California: Altadena, a small, unincorporated town nestled between Pasadena and the San Gabriel Valley to the south and the mountains of the Angeles National Forest to the north and east.

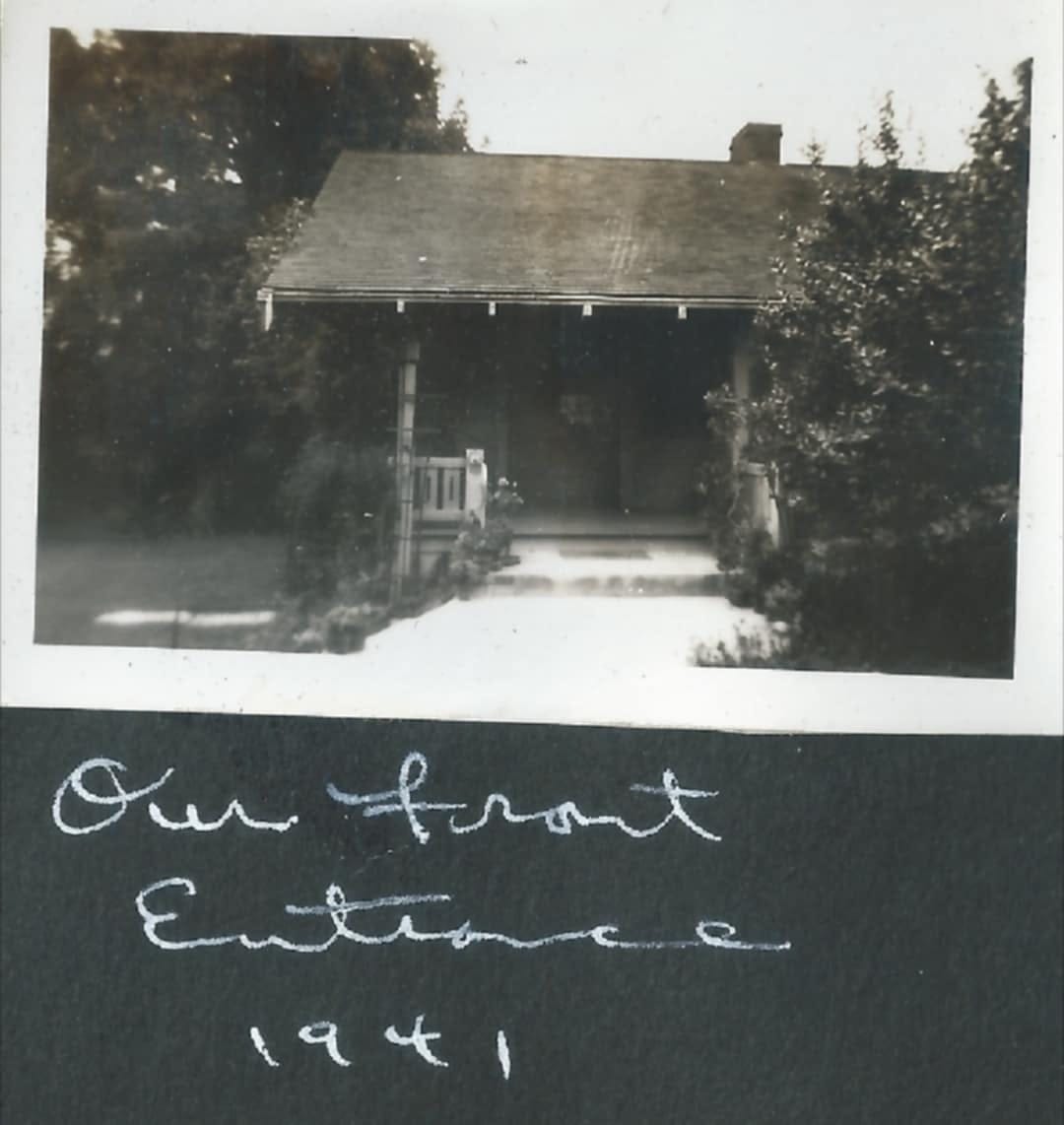

Dotted with orange trees and towering palms, Armenian bakeries and soul food restaurants, Altadena is where my father grew up and a place I’ve visited all my life. My grandmother Sara moved there from New York with her family in 1933 when she was five years old. With a few exceptions—college in Oakland, a few years in Florida with my paternal grandfather, a marine biologist, after which she returned alone, with two small children—she lived in the same WWI-era home for almost 90 years.

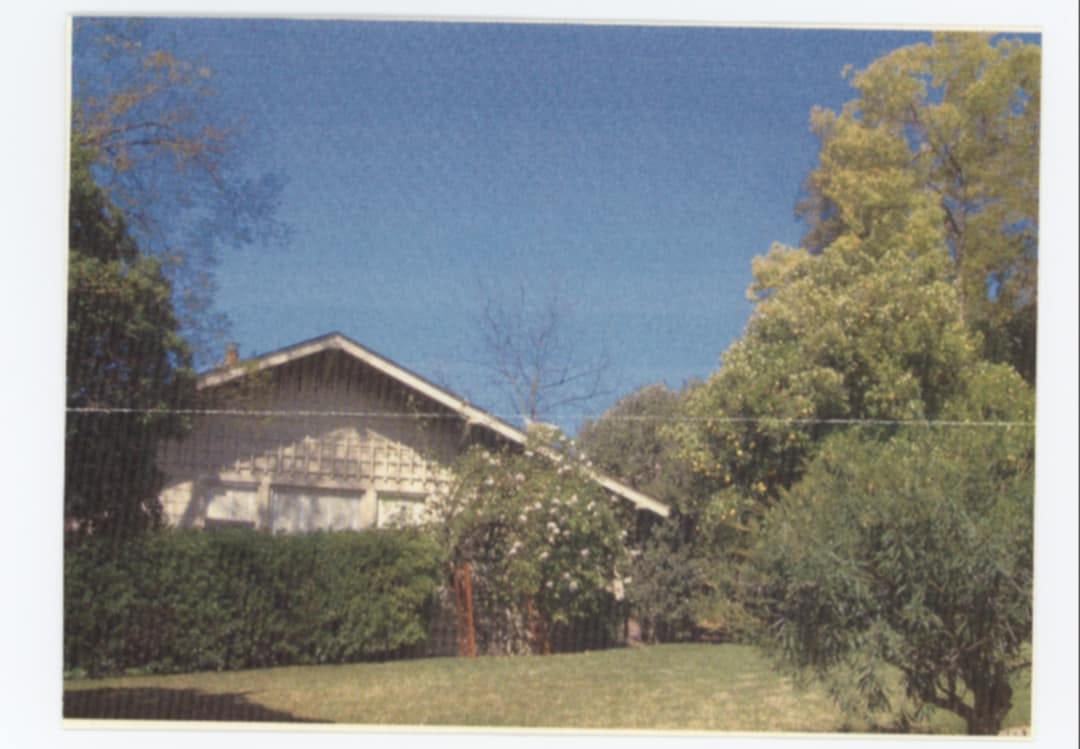

The house on Highland Avenue was a sand-colored, single-story Craftsman in a sea of green. A steep staircase to an upstairs room had been added on at some point, and a dark, dusty garage crammed with old tools sat at one end of the long, narrow driveway. There was a shady porch, large, heavy doors, and original features like built-in shelving and star-patterned linoleum in many of the rooms. But it was the gardens, where fruit and flowers seemed to flourish without effort, that always fascinated me.

A massive camellia, an orange tree, and a feijoa tree in the front edged a sprawling lawn of stiff, scrubs-green grass. The spindly palm at the curb was the tallest on the block. The backyard bore tangerines, walnuts, kumquats, Bearss limes, lemons, more oranges, and white grapefruits, which collected on the shady ground below in heaps, molding fuzzy blue and green.

There were two towering avocado trees, plus rose bushes, patches of calendula and violets, and an ancient, gnarled wisteria vine shading the back porch. For years after my parents settled on the East Coast in the ’90s, Grandma would pull out her picking pole and laundry basket to harvest the scaly avocados, wrap each in newspaper, and ship them across the country for us to mash on toast with salt, pepper, and lemon juice.

I was nine when my parents and I left California to follow my dad’s job to North Carolina. We visited Grandma’s house at Christmas or summertime most years when I was a kid and a teen. When my partner and I began visiting my grandmother on our own around 2015, I hadn’t been to California in several years; I was a broke college student, then a broke twentysomething.

Because my visits were mediated through my grandmother’s or my father’s experiences and landmarks and routines, stopping by the same old haunts and old friends’ houses every visit, and because the house on Highland stayed the same from year to year, Altadena could seem unchanged when seen for a week or two at a time over decades.

The drugstore where my father worked as a delivery boy, Webster’s, was still there. Businesses that had stood since the ’60s still displayed their original signage. The cute little bungalows and Spanish-style ranchitas and sprawling mansions built in the first half of the 20th century gave the place a distinct character. Despite the forces of gentrification and skyrocketing housing costs, Altadena was still home to many working class and middle-class families—notably, it was one of the few places in the LA area where Black families could purchase homes in the days of racist redlining.

But gradually, the economic forces that had long shaped the entire region became more apparent, more visible. Home values had soared. New neighbors moved in: Disney executives, UCLA professors, and mid- to low-level celebrities you may have actually heard of—Mandy Moore, Maria Bamford.

Coffee shops and smoothie places popped up among the longstanding Mexican restaurants and thrift shops. A wood-fired pizza and natural wine spot opened up at the corner of Lake and Altadena, and bougie young families flocked to the oyster shuckers and arepa trucks at the weekly farmers’ market in a nearby park. As these markers of gentrification multiplied and the socioeconomic status of each wave of new residents became wealthier, my grandmother scoffed, bemused at the idea that people would be willing to pay so much to live in the place she thought she’d never leave.

When I was a kid in California, we were warned more about earthquakes than fires. Whenever there were fire warnings in the mountains above her home, Grandma would wave them off—the flames never came that far down the foothills, she’d say. In 2020, when the Bobcat Fire put my grandmother’s street one zone away from mandatory evacuation, I asked my dad what the plan was. There wasn’t one, aside from hoping the able-bodied neighbors who kept tabs on her would have space in the car and presence of mind to get her out.

My parents, in their retirement, had wanted to move out there with her, to return to the California where they met in the early ’80s, when they lived by the beach and sold encyclopedias door to door. We all envisioned keeping the house on Highland in the family. When my nephews were born in North Carolina, that plan changed. Grandma was still hanging in there, getting around okay with help from neighbors and rides to Trader Joe’s from friends, despite her poor hearing and low vision. After all, Great Grandma lived to be 101 and a half, as she often reminded us.

So her children waited. Grandma didn’t want to leave, and they didn’t want to go. And no one thought the flames would ever come that close.

The decision the family had refused to make was made for us. In 2021, my grandmother broke her hip. She tripped on the dangling electrical cord from the device she used to brighten and enlarge documents, an analog contraption that looked a bit like an old-timey overhead projector. It had been in that same spot for years.

My dad and his brother flew out to transition her from hospital to rehab to assisted living. By the following year, it was determined that the retirement savings her second husband had left her were running low, and the house that had been in our family for nearly a century would have to be sold.

Family members took items that held monetary or sentimental value. I received a TV my grandma never watched, a cedar chest full of wool blankets, a cracked ceramic mixing bowl, and a handmade wooden dresser given to my suffragette great-grandmother by Eleanor Roosevelt.

The rest was sold off in an estate sale. My dad sent me a video promoting the sale, showing an unrecognizable living room heaped with a century’s worth of possessions, grouped by item into piles of teacups, tchotchkes, cookware. I couldn’t watch for long. I didn’t want to see a life, generations of a family, a place that maybe could have kept my grandmother more lucid, content, even happy had she been able to continue aging in place, prepared to be picked over by resellers. To see a place that had been such a constant in my and my family’s life since before any of us were born become unfamiliar and strange.

There would be no more visits to Altadena. No hikes in Eaton Canyon or strolls up and down the steep 6% grade of Highland Avenue with my grandmother. No more avocados.

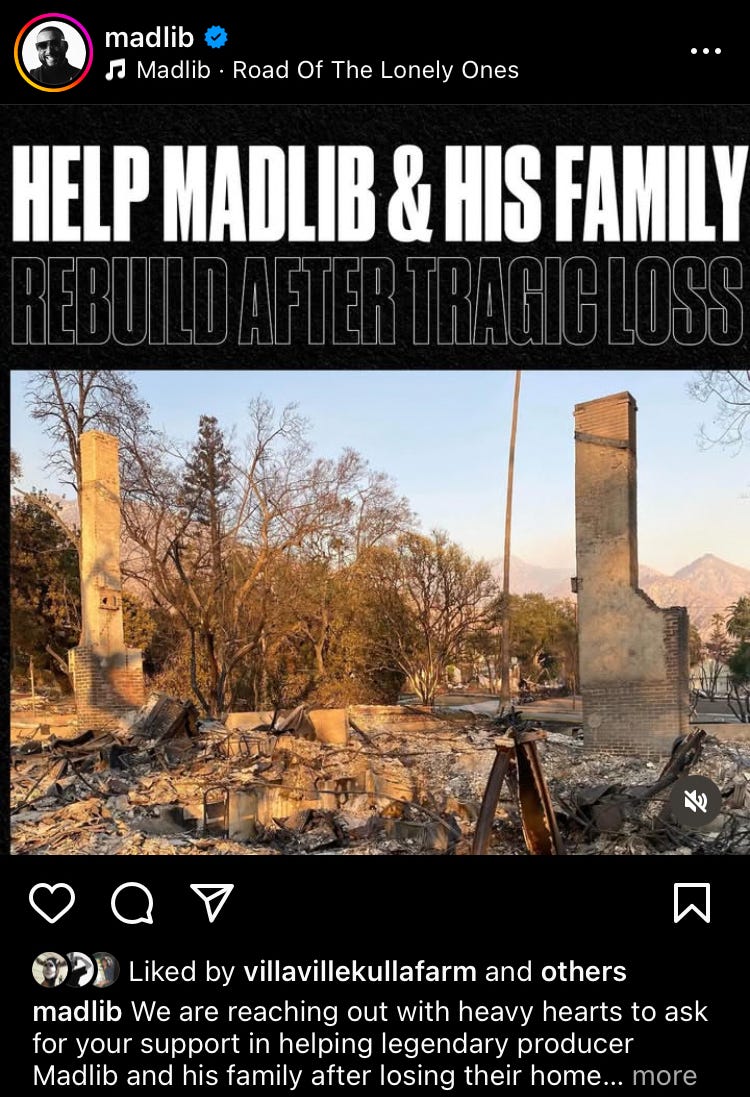

The house sold for a $1.85 million—an unimaginable sum to me and most people I know, but not for the LA housing market, especially if you work in entertainment. The person who bought it was the DJ and producer Madlib. You know who he is if you’ve even casually followed rap music over the last few decades; if not, trust that he’s an icon. Selling your grandma’s house to some form of celebrity is, I suppose, an everyday occurrence in Southern California.

This was, all things considered, a best case scenario. My grandmother could pay for her assisted living facility with the proceeds after closing costs and taxes and fees. Whatever’s left will go to my dad and uncle, and if anything remains when they’re gone, it’ll trickle its way down to me and my sister and my cousins. Isn’t that how the American dream of homeownership is supposed to work?

Still, there was grief in letting go of a place that held such value as a piece of family history, as a tie connecting the family to California, as a reminder of our respective childhoods, as a sunny and unchanging constant in our lives, not just a financial asset. Now a new family would make a home there. We’d have the peace of mind that Grandma was taken care of and maybe some inherited wealth and a fun fact to share about the whole thing. Wasn’t it crazy that Madlib would be making beats in the basement where my father and uncle had band practice with their high school buddies?

Now Altadena as any of us knew it is gone. My grandmother has outlived her hometown. I saw a satellite map of the fires, which someone had overlaid with street names. The fifth house down on Highland Avenue, west side of the street, where multiple generations of my family had called home, was just one in a line of small red embers. A neighbor shared a video with one of my dad’s childhood friends, showing the footprints where houses once stood, flattened to gray, smoldering rubble, but it didn’t show Grandma’s house. We knew there was no way it could have survived. There were stories of houses that did, and of people who died, garden hoses in hand, trying and failing to save the homes they’d lived in for decades.

We got confirmation in the form of a since-deleted Instagram post, taken from somewhere around the southwest corner of the house that was my grandmother’s bedroom. The orange and feijoa are charred and leafless. The palm, a headless twig in the background of the image, is still standing. No word on the avocado trees.

It’s not just my grandmother’s house that’s gone. It’s the entire community where she lived for almost a century, where my father grew up, where thousands of people lived and worked and went to school and church and the store and everything else. The Eaton Fire consumed much of the foothill town, destroying more than 9,000 homes in Altadena and Pasadena and killing 17 people there—deaths that could have been avoided if residents in the working-class neighborhoods on the other side of Lake Avenue had been told to evacuate in time.

Our family grieved when we had to sell the house. My dad and uncle lost their childhood home. My grandmother lost one of the last things that still made her who she was, the place she knew by heart. I lost the closest thing I had to a real place, not an abstract foreign past, where her old stories could feel real. The place I’d first marveled at trees laden with fruit, the idea that food could be so abundant as to be unremarkable, plucked from the branch or gathered from the ground on a whim. But at least we had the chance to say goodbye.

Our family was lucky, if luck can be said to exist in the time of climate change. Our intangible, emotional losses were balanced by a tangible financial benefit. We’d gotten out while we could. The house had been sold. Grandma wasn’t there—she almost certainly wouldn’t have survived. We hadn’t had the most valuable thing anyone in the family owned—shelter, safety, history, memories—turn to ash overnight.

The fire brought on a new wave of grief, one that feels crass to write about in light of what so many people have lost in the fires. Homes and jobs and everything they owned and loved ones and lives.

By now, I’m used to watching disasters unfold secondhand through my phone, through friends or relatives or strangers on social media more than through news outlets. Small farms in Vermont inundated by floodwaters during peak harvest season. Businesses in Florida cataloging the damage after hurricanes. People sharing photos of mountain towns just washed away, posting about which on-the-ground mutual aid groups or community-led recovery initiatives to Venmo.

The fire that burned Altadena combined that suppressed panic and empathy and powerlessness with echoes of a deeply personal loss and some dilute form of survivor’s guilt. It’s a new kind of climate grief for me, and I’m sure not the last permutation I’ll experience.

I don’t know what else to say about the Eaton Fire that hasn’t been said in news articles or Instagram stories about Octavia Butler or the quote (which I can’t find attribution for) that “climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.”

Except that while I bore witness to this integral piece of my family’s story going up in literal flames through social media, I also saw that how governments and institutions handle this fire recovery will be the biggest indication of how they’ll deal with disaster when it comes to your community. I saw that the people in these communities were the ones helping to protect themselves and their neighbors from fire, organizing clothing and supply drives, preparing and giving away food, and distributing masks to protect against the toxic air.

The actions and inaction of our governments and institutions and corporations got us into this mess. Now that we’re stuck in it, they refuse to adequately prepare or fund the efforts that can save property and landscapes and lives from this devastation, or reduce its impact, or help us recover when the smoke clears. We will be the ones sifting through the rubble and collecting donations and checking on neighbors and providing for each other. If we’re lucky.

I can't imagine how hard this was to write. It is such a beautiful tribute to your families home, and also a stark reminder to all of us that these events are seen all too often, and more and more frequently. Our leaders and those in power have really let us down, and continue to do so. So we take care of each other. You brought me to tears.

So terrible for your family, and all the others. Especially your grandma and the Madlib family, and all grandma's old neighbors. So much has been lost.

Love to all.